Interstellar Review: Boldly Going

Interstellar Review (spoiler-free, honest!)

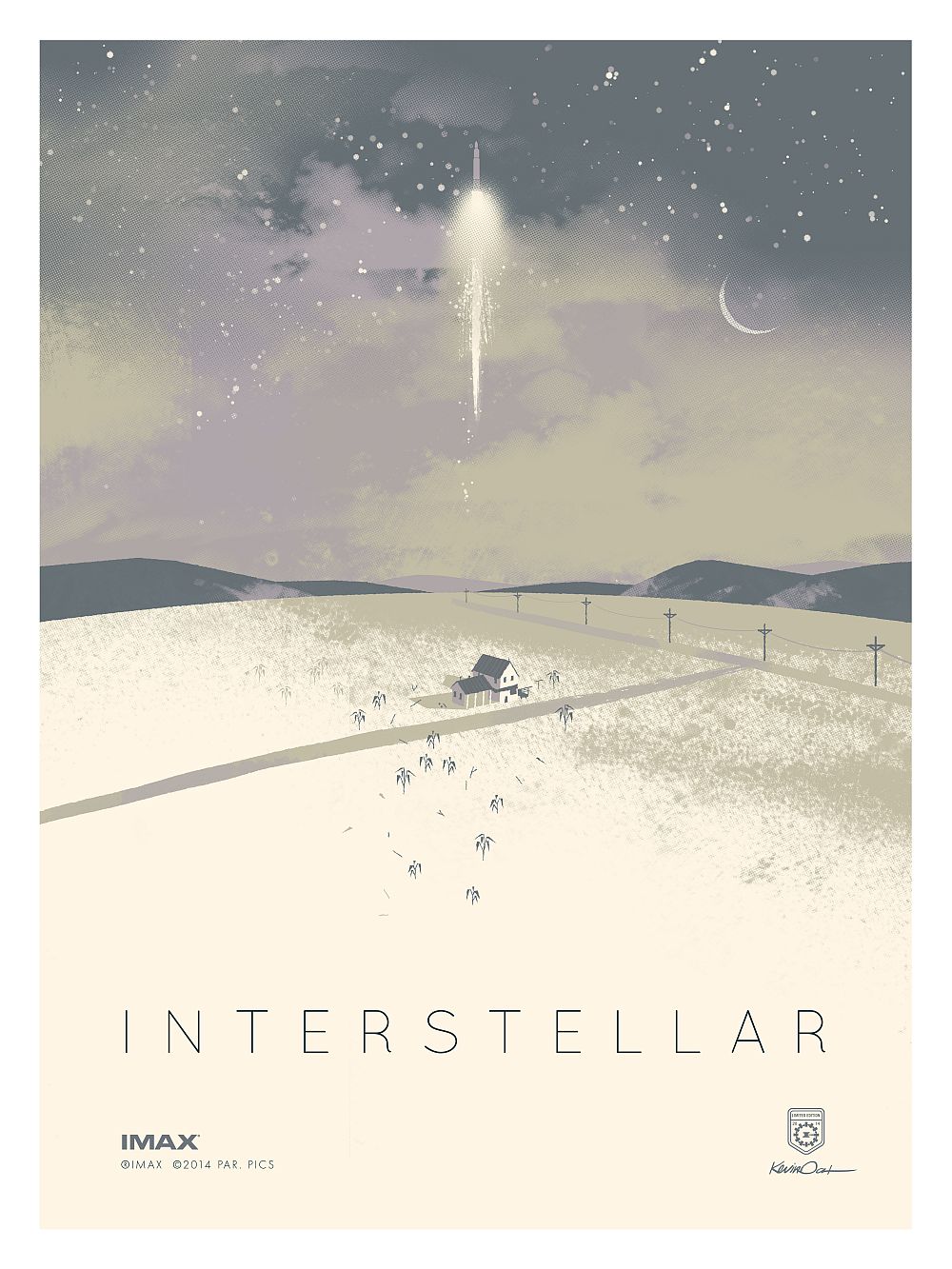

The recurring note within Interstellar is the W.H.Auden poem, a plea to not go quietly toward death, but to "rage, rage against the dying of the light." It's a call to arms for life, to not shuffle off the mortal coil, but to fight, fight, and fight some more, until your dying breath, and with your dying breath. Story-wise, this fits the movie perfectly. Our world and our species on the brink of a slow, agonizing departure, the hero fights, almost beyond death, to save everything he holds dear, everything any of us hold dear. It's an epic journey that takes us from dying cornfields plagued by titanic dust-storms, out into the depths of our solar system, beyond it to another galaxy, and beyond even time and space itself, into the realms of the philosophical and the esoteric.

However, as a movie and as an endeavour, Interstellar is probably better served by Robert Browning's famous lines in his poem, Andrea del Sarto: "Ah, but a man's reach should exceed his grasp, Or what's a heaven for?" For Interstellar is nothing, if not a master film-maker, at the top of his game (his game so far, tantalizingly), reaching literally for the heavens, and not quite being able to hold it in his hands.

The ambition of Interstellar verges on the ludicrous. A gigantic, intellectually-driven, journey into the edges of space. Where other movies would cower and take the off-ramp into comfortable genre, Interstellar powers on. To see a movie that even touches on the subject matter and themes with which Interstellar deals would be goal enough. To see it march on, shoulder the weight of its responsibilities to the story and cross the finish line, is simply breath-taking. In terms of scope, this is a fearless film. It charts a course to the edge of that which cinema is capable, and unflinchingly, unswervingly, follows that path. Nothing in Nolan's pristine back-catalogue comes close to what Interstellar attempts. And it is in the attempt, the reach, and the not quite grasping of the prize, that Interstellar falls short.

Is the film a failure? If it is, it's only by the standards of its own colossal ambition. The story that the Nolans (no, not the sister act from Ireland, but writer-director Christopher, and his brother Jonah) attempt to land is on the 2001 scale. It is attempting to reach further and higher than any movie has any right to. It is attempting to transcend not just the ordinary, but also the extra-ordinary, into the truly theoretical, ethereal, and spiritual - whatever that is to you. In the final act, it is touching the realm where the edge of science meets the philosophical. If Nolan was making action movies with A Levels with the Batman trilogy, and action-thriller with a degree in Inception, he's making drama with a Ph.D. in Interstellar. Like Inception, you walk out with your head spinning, dazzled by the spectacle you've just witnessed (especially in Imax), disbelieving that any film-maker is attempting story-telling that requires so much from an audience.

The influences here are apparent and Interstellar wears them readily on its flight suits. 2001 is weaved into the fabric of this movie, with even a sly nod to it in the form of one of the robots joking that he will blast McConaughey's pilot, Cooper, out of an airlock. Hans Zimmer's score also beats you about the head with the comparison, stopping short of using Also Sprach Zarathustra (the duun, duun, duun - DA DAA!) or the Blue Danube Waltz. Other knowing winks are thrown at Silent Running, Douglas Trumbull's 1972 movie about an astronaut obsessively and murderously saving the last plant life from Earth. The robots in Interstellar clearly link back to Huey, Duey, and Looie from Trumbull's film. The biggest nod comes via the casting of Matthew McConaughey though, to one of his earlier movies (before his badly misjudged detour into rom-com territory, and way before his renaissance), Contact. Remember that jaw-dropping opening scene? In Contact, McConaughey played the religious role, skeptical of Jodie Foster's belief in the limitless reach of science. Here, he's much more in Foster's character's role - a pilot and engineer, desperate to use all the accumulated knowledge of the world to save it. He's a man of science, driven by the most human of motivations - to save his family, and most notably, his daughter.

While McConaughey's casting is faultless, and his performance will do nothing to diminish his current supernova-esque brightness, some of the supporting members feel like a case of casting a star for the sake of it. Anne Hathaway puts in a solid performance, but doesn't add much weight to the proceedings. Her short speech about love being the most powerful force in the universe would be hard for anyone to pull off, but it's one of the poorer notes during the film. Jessica Chastain is under-used and looks like she walked off the set of Zero Dark Thirty. Similarly, Casey Affleck does what he can with the little he's given, but it's hard to escape the feeling that this would have been better served by a solid, unknown, character actor. John Lithgow and Michael Caine perform their duties admirably, but again, when you have actors of this calibre, you want to see them stretch their legs and show you what they can do. As it is, seeing them on-screen doing so little is frustrating. The worst miscast is the "secret", unbilled, AAA Hollywood star that appear halfway through the film. The role itself is substantial and critically important, but the casting is distracting. In a moment that should be all about the moment itself, the literal unzipping of this character had me immediately replaying YouTube moments in my head. It's hard to say more without revealing it, but you'll know it when you see it.

This miscast is symbolic of the biggest issue Interstellar has - is it a blockbuster trying to be an arthouse film, or the other way around? Given the $165m budget, filling multiplexes was clearly key, but the film never quite comfortably wrestles the intellectual, emotional, and the action to the ground. Unlike 2001 and Contact, both of which stayed within the spheres in which they had placed themselves, Nolan is clearly trying to please everyone - the blockbuster spectacle cinema-goers, the devoted arthouse cineastes, and crucially, the studio paying the bills. This was something he pulled off with Inception, but the weight of the subject matter in Interstellar is far greater, leading to a larger gulf between the sublime and the superficial. While the story and the themes demand serious focus, Nolan is forced to inject pyrotechnics where none are called for. The whole middle section - which culminates in the movie's big action set-piece - comes across as a placatory move to the studio. It crosses into Gravity territory, going for reliable, audience-pleasing spectacle, but dampening the human drama that is the driving force of the rest of the film. But without it, perhaps getting any studio exec to hand over that big a cheque would have been unrealistic. But if Nolan can't do it, who can?

Ultimately though, this is a movie that must be seen, if only for the audacity of its intention. Interstellar's ambition mirrors that of its protagonist. We start in the dirt, ascend into the sky, soar into a distant galaxy, and emerge within our imagination. No one else is doing this, or is able to do this. Interstellar is yet another quantum (physics) leap beyond the intelligent sci-fi movies which have been returning to our screens - be it Nolan's own Inception, Gravity, Snowpiercer, Edge of Tomorrow, etc. In tackling a story this far-reaching, it's pushing the boundaries of what visual story-telling can achieve. At times, you feel the screen starting to buckle under the weight of what it is trying to convey. And for the most part, the screen holds fast.

Interstellar deserves a place in cinematic history. Its few and forgivable faults are understandable - the scale of its ambitions sometimes over-shoot its capabilities to depict; the necessity of the budget requires commerce to overpower creative. But Interstellar should ultimately be judged not by how much it achieves, but how much it strives for. Its reach truly exceeds its grasp. But to witness a movie even reach this far is something truly special indeed.

The recurring note within Interstellar is the W.H.Auden poem, a plea to not go quietly toward death, but to "rage, rage against the dying of the light." It's a call to arms for life, to not shuffle off the mortal coil, but to fight, fight, and fight some more, until your dying breath, and with your dying breath. Story-wise, this fits the movie perfectly. Our world and our species on the brink of a slow, agonizing departure, the hero fights, almost beyond death, to save everything he holds dear, everything any of us hold dear. It's an epic journey that takes us from dying cornfields plagued by titanic dust-storms, out into the depths of our solar system, beyond it to another galaxy, and beyond even time and space itself, into the realms of the philosophical and the esoteric.

However, as a movie and as an endeavour, Interstellar is probably better served by Robert Browning's famous lines in his poem, Andrea del Sarto: "Ah, but a man's reach should exceed his grasp, Or what's a heaven for?" For Interstellar is nothing, if not a master film-maker, at the top of his game (his game so far, tantalizingly), reaching literally for the heavens, and not quite being able to hold it in his hands.

The ambition of Interstellar verges on the ludicrous. A gigantic, intellectually-driven, journey into the edges of space. Where other movies would cower and take the off-ramp into comfortable genre, Interstellar powers on. To see a movie that even touches on the subject matter and themes with which Interstellar deals would be goal enough. To see it march on, shoulder the weight of its responsibilities to the story and cross the finish line, is simply breath-taking. In terms of scope, this is a fearless film. It charts a course to the edge of that which cinema is capable, and unflinchingly, unswervingly, follows that path. Nothing in Nolan's pristine back-catalogue comes close to what Interstellar attempts. And it is in the attempt, the reach, and the not quite grasping of the prize, that Interstellar falls short.

Is the film a failure? If it is, it's only by the standards of its own colossal ambition. The story that the Nolans (no, not the sister act from Ireland, but writer-director Christopher, and his brother Jonah) attempt to land is on the 2001 scale. It is attempting to reach further and higher than any movie has any right to. It is attempting to transcend not just the ordinary, but also the extra-ordinary, into the truly theoretical, ethereal, and spiritual - whatever that is to you. In the final act, it is touching the realm where the edge of science meets the philosophical. If Nolan was making action movies with A Levels with the Batman trilogy, and action-thriller with a degree in Inception, he's making drama with a Ph.D. in Interstellar. Like Inception, you walk out with your head spinning, dazzled by the spectacle you've just witnessed (especially in Imax), disbelieving that any film-maker is attempting story-telling that requires so much from an audience.

The influences here are apparent and Interstellar wears them readily on its flight suits. 2001 is weaved into the fabric of this movie, with even a sly nod to it in the form of one of the robots joking that he will blast McConaughey's pilot, Cooper, out of an airlock. Hans Zimmer's score also beats you about the head with the comparison, stopping short of using Also Sprach Zarathustra (the duun, duun, duun - DA DAA!) or the Blue Danube Waltz. Other knowing winks are thrown at Silent Running, Douglas Trumbull's 1972 movie about an astronaut obsessively and murderously saving the last plant life from Earth. The robots in Interstellar clearly link back to Huey, Duey, and Looie from Trumbull's film. The biggest nod comes via the casting of Matthew McConaughey though, to one of his earlier movies (before his badly misjudged detour into rom-com territory, and way before his renaissance), Contact. Remember that jaw-dropping opening scene? In Contact, McConaughey played the religious role, skeptical of Jodie Foster's belief in the limitless reach of science. Here, he's much more in Foster's character's role - a pilot and engineer, desperate to use all the accumulated knowledge of the world to save it. He's a man of science, driven by the most human of motivations - to save his family, and most notably, his daughter.

While McConaughey's casting is faultless, and his performance will do nothing to diminish his current supernova-esque brightness, some of the supporting members feel like a case of casting a star for the sake of it. Anne Hathaway puts in a solid performance, but doesn't add much weight to the proceedings. Her short speech about love being the most powerful force in the universe would be hard for anyone to pull off, but it's one of the poorer notes during the film. Jessica Chastain is under-used and looks like she walked off the set of Zero Dark Thirty. Similarly, Casey Affleck does what he can with the little he's given, but it's hard to escape the feeling that this would have been better served by a solid, unknown, character actor. John Lithgow and Michael Caine perform their duties admirably, but again, when you have actors of this calibre, you want to see them stretch their legs and show you what they can do. As it is, seeing them on-screen doing so little is frustrating. The worst miscast is the "secret", unbilled, AAA Hollywood star that appear halfway through the film. The role itself is substantial and critically important, but the casting is distracting. In a moment that should be all about the moment itself, the literal unzipping of this character had me immediately replaying YouTube moments in my head. It's hard to say more without revealing it, but you'll know it when you see it.

This miscast is symbolic of the biggest issue Interstellar has - is it a blockbuster trying to be an arthouse film, or the other way around? Given the $165m budget, filling multiplexes was clearly key, but the film never quite comfortably wrestles the intellectual, emotional, and the action to the ground. Unlike 2001 and Contact, both of which stayed within the spheres in which they had placed themselves, Nolan is clearly trying to please everyone - the blockbuster spectacle cinema-goers, the devoted arthouse cineastes, and crucially, the studio paying the bills. This was something he pulled off with Inception, but the weight of the subject matter in Interstellar is far greater, leading to a larger gulf between the sublime and the superficial. While the story and the themes demand serious focus, Nolan is forced to inject pyrotechnics where none are called for. The whole middle section - which culminates in the movie's big action set-piece - comes across as a placatory move to the studio. It crosses into Gravity territory, going for reliable, audience-pleasing spectacle, but dampening the human drama that is the driving force of the rest of the film. But without it, perhaps getting any studio exec to hand over that big a cheque would have been unrealistic. But if Nolan can't do it, who can?

Ultimately though, this is a movie that must be seen, if only for the audacity of its intention. Interstellar's ambition mirrors that of its protagonist. We start in the dirt, ascend into the sky, soar into a distant galaxy, and emerge within our imagination. No one else is doing this, or is able to do this. Interstellar is yet another quantum (physics) leap beyond the intelligent sci-fi movies which have been returning to our screens - be it Nolan's own Inception, Gravity, Snowpiercer, Edge of Tomorrow, etc. In tackling a story this far-reaching, it's pushing the boundaries of what visual story-telling can achieve. At times, you feel the screen starting to buckle under the weight of what it is trying to convey. And for the most part, the screen holds fast.

Interstellar deserves a place in cinematic history. Its few and forgivable faults are understandable - the scale of its ambitions sometimes over-shoot its capabilities to depict; the necessity of the budget requires commerce to overpower creative. But Interstellar should ultimately be judged not by how much it achieves, but how much it strives for. Its reach truly exceeds its grasp. But to witness a movie even reach this far is something truly special indeed.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home